The 1992 Presidential Election and the Rise of Democratic Populism

Written by: Chester Pach, Ohio University

By the end of this section, you will:

- Explain the causes and effects of continuing policy debates about the role of the federal government over time

Suggested Sequencing

Use this narrative with the Maya Angelou, “On the Pulse of Morning,” January 20, 1993 Primary Source and the Republican House Representatives, “Republican Contract with America,” 1994 Primary Source after covering the Cold War to discuss post-Cold War domestic politics.

At the end of the Persian Gulf War, President George H. W. Bush seemed certain to win a second term. After only six weeks of airstrikes and 100 hours of ground fighting, U.S. troops, along with their coalition partners, had won an overwhelming victory over Iraq when combat operations ended on February 27, 1991. A record 89 percent of the American people approved of Bush’s performance in office. No preceding post-World War II president had ever achieved such a high level of public support in the Gallup Poll.

President George H. W. Bush visiting troops deployed in Saudi Arabia in November 1990, during the Persian Gulf War.

Bush’s popularity did not last, however. The economy sank into recession in late 1990. By the middle of 1991, the unemployment rate had climbed to 7.8 percent, the highest level since the early 1980s. When Bush announced he was running for a second term in February 1992, his approval rating had plunged to 41 percent. When he accepted the Republican presidential nomination at the party’s national convention in Houston in July, only 29 percent of the American people thought he was doing a good job as president.

The American people usually credit a president for prosperity and blame a president for economic problems, and Bush’s own actions added to popular discontent with him. The White House refused to admit there was a recession until late 1991, even though Bush had spoken privately for months about the downturn in the economy that had cost millions of Americans their jobs. He vetoed a bill that would have increased unemployment insurance benefits, claiming that new spending would add to the problem of a growing federal deficit. During a visit to a Florida supermarket, he expressed amazement at a barcode scanner, already a common sight at checkout counters. These actions made Bush appear to be out of touch with the lives of ordinary Americans and the grievous effects of the recession. They seemed to confirm his image as a wealthy elitist, even though people who knew him praised his graciousness and generosity.

The election witnessed the crest of a wave of populism, as many ordinary Americans came to believe that their problems were caused by cultural and economic elites. Americans blamed elites for the disappearance of high-paying manufacturing jobs, increasing economic inequality, and changing values in media. The tensions worsened with a deep economic recession in 1991and populist frustration and anger turned into a political revolt against elites in both parties and the popularity of third-party candidates.

Bush faced a challenge for the Republican presidential nomination from Patrick J. Buchanan, a fiery populist who had served as President Ronald Reagan’s director of communications before hosting the popular current affairs show Crossfire on CNN. Buchanan rallied enthusiastic supporters, known as Pitchfork Brigades, with his denunciations of “King George.”

Pat Buchanan (center, shaking hands) at a political rally in 1992.

Bush was vulnerable to a challenge from the right because he had broken his famous campaign promise from 1988, when he declared, “Read my lips: no new taxes.” Two years later, to comply with legislation that required the lowering of the federal deficit, he had approved an increase in income taxes. Claiming that Bush was no conservative true believer, Buchanan captured 34 percent of the vote in the New Hampshire primary. That suggested he had no chance of winning the nomination, but he refused to drop out of the race and continued to stoke populist discontent on the right.

Bush, for his part, ran a bland campaign. His chief strategist in 1988, Lee Atwater, died of a brain tumor in 1991. Bush had his own health problems, including an irregular heartbeat. His most visible health calamity, however, produced more ridicule than sympathy. During a trip to Japan in January 1992, he contracted an intestinal virus and vomited on Prime Minister Kiichi Miyazawa. Television showed the videotape endlessly, sometimes with sneering commentary. At times, Bush privately confessed little enthusiasm for running another campaign but always concluded that he had to finish the job he had begun.

Economic populism fueled the candidacy of Bush’s Democratic challenger, Governor Bill Clinton of Arkansas. Clinton fashioned himself as a “New” Democrat. In 1985, he helped found the Democratic Leadership Conference, which aimed at moving away from the old-fashioned liberalism that had led to Walter Mondale’s crushing defeat in the presidential election of 1984. Clinton and the New Democrats wanted to preserve their party’s commitment to social responsibility while moving toward the political center. In Arkansas, Clinton had improved education and health care while working with business to foster economic development and job growth.

As he contemplated a run for the presidency, Clinton laid out his vision of economic reform in a series of “Covenant Speeches” at Georgetown University. He proposed to renew the bond between “the people and their government” by paying more attention to “forgotten middle-class Americans” who had failed to gain in income or status while the rich had secured a greater share of national wealth. Clinton decried the Republicans’ “failed experiment in supply-side economics” but also understood that Reagan had changed popular thinking about the scope of big government. There would “never be a government program for every problem,” Clinton emphasized, but a more efficient government could help those in need by making welfare into a temporary program that trained people to get a job and support themselves. As Clinton won the primaries that carried him to the Democratic nomination for president, his staff devised a slogan that expressed the central issue of his campaign: “It’s the economy, stupid.”

Complicating the campaigns for both Clinton and Bush was the on-again, off-again third-party candidacy of billionaire business owner H. Ross Perot. Perot had acquired a huge personal fortune from a data processing company, and this made his independent bid for the presidency possible. He had taken a special interest in Americans who were prisoners of war or missing in action in Vietnam, and during the Reagan administration, he insisted that the government had not done enough to ensure a full accounting of their fates. As his criticisms became more extreme, then Vice President Bush had the task of informing Perot that the administration would cease cooperating with him. Perot carried a grudge. One campaign aide declared that if Perot could prevent Bush’s reelection, he would be “on top of the world. He hates George Bush.”

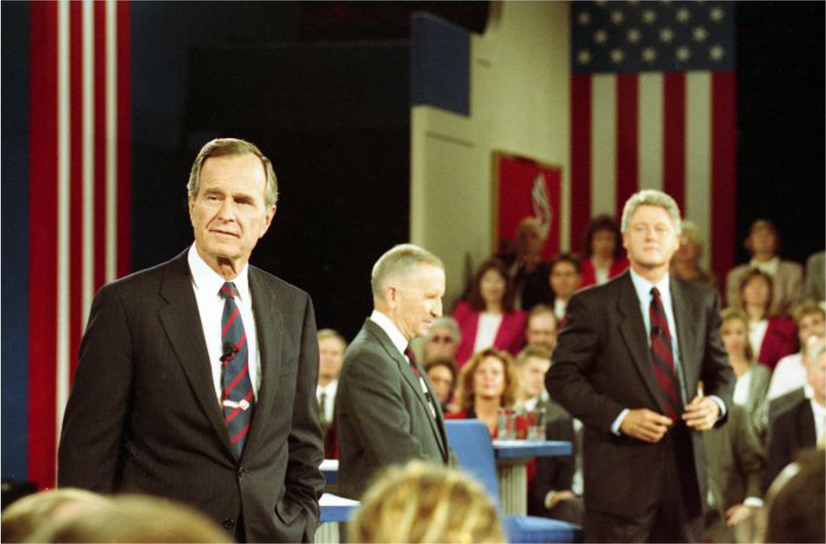

During the 1992 presidential election, (right) Ross Perot ran one of the most successful third-party campaigns in U.S. history. Perot is shown here with (center) President Bush and (left) Governor Bill Clinton during the third and final presidential debate in 1992.

Perot created interest in his candidacy through his shrewd use of television. As a frequent guest on CNN’s Larry King Live, he announced he would run for president if his supporters filed petitions that would get him on the ballot in all 50 states. Perot had a prickly personality, but his supporters liked his no-nonsense, outsider image at a time when Washington politics seemed to produce scandal, deadlock, and recession. Perot suggested there were simple solutions to the nation’s complex problems. He said he aimed to get the best people, whoever they might be, to figure out solutions and implement them. Perot likened himself to a carpenter in crafting public policy solutions. He would “measure twice and cut once.”

Perot’s career as a successful business leader made him an appealing figure during an economic downturn. So, too, did his skillful opposition to the proposed North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). The Reagan administration had already secured a free-trade agreement with Canada; Bush hoped to add Mexico, and NAFTA negotiations were occurring during the election year of 1992. Perot warned that NAFTA would threaten American jobs at a time when the economy was just beginning to recover. Thanks to Mexico’s lower wages and less restrictive government regulations, he said, U.S. jobs would drain south with a “giant sucking sound.”

Perot was riding high in the polls when he suddenly announced in July that he was withdrawing from the race. He claimed he did not want to be responsible for an election that had no winner and that required the House of Representatives to choose the next president. Then, just as abruptly, he reentered the race in October. Polls suggested he would indeed siphon votes away from both Bush and Clinton. Bush could ill afford any such losses. He was trailing Clinton by double digits in the polls, and 78 percent of the American people believed that under him, the country was moving in the wrong direction.

When the three candidates met in Richmond, Virginia, on October 15 for a debate, economic concerns were at the center of discussion. An audience of undecided voters posed the questions. A young woman asked Bush about how the recession had affected him personally. Bush began by looking at his watch and then rambled on about the unfairness of assuming that someone who was prosperous could not understand the plight of the unemployed. Clinton walked up to the questioner and explained how as governor of a small state, he knew the names of workers who had lost their jobs and factory owners who had closed their businesses. He then condemned the past “twelve years of trickle-down economics” that he claimed had slowed job creation and eroded wages. Clinton’s political skills – and Bush’s lack of them – made it seem as if Clinton cared about ordinary Americans and Bush did not. The economy was already recovering when the debate occurred, but that hardly seemed to make a difference.

President George H. W. Bush (left), independent candidate Ross Perot (center), and Democratic candidate Bill Clinton (right) at the 1992 presidential debate in Richmond, VA.

Clinton won the election handily over Bush by a margin of 370-168 electoral votes. Perot received no electoral votes but won 19 percent of the popular vote – an astounding amount for an independent candidate. Meanwhile, Clinton won 43 percent of the popular vote, whereas Bush finished second with 37 percent. “The common wisdom is that I’ll win in a runaway but I don’t believe that,” Bush wrote in his diary on March 18, 1991. “I think it will be the economy [which] will make that determination.” The election of 1992 proved he was right.

Review Questions

1. New Democrats such as Bill Clinton shifted the focus of the party because they believed Democrats should

- cooperate more often with Republicans

- position themselves at the political center rather than on the left

- make stronger efforts to help the poor and give less attention to middle-class issues

- adopt more Republican ideas, like supply-side economics

2. In 1992, the main issue for independent presidential candidate Ross Perot was

- the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)

- high taxes

- the death penalty

- unemployment insurance

3. Approaching the 1992 presidential campaign, President George H. W. Bush looked poised to win a second term because of

- his appeal as a working-class populist candidate

- his vetoing of legislation that would add to the federal deficit

- his handling of the Persian Gulf War

- the strength of the American economy in the early 1990s

4. As presidential candidates, Bill Clinton and Richard Nixon both centered their campaigns on political appeals to the

- “forgotten” middle-class voter

- young urban professional (“yuppie”) voter

- upper-class white voter

- poor, rural Sun Belt voter

5. The North American Free Trade Agreement begun by Ronald Reagan and finalized by Bill Clinton most clearly illustrates that

- Ross Perot’s concerns about it were unfounded

- it is impossible for multiple countries to reach economic agreements

- dependence on foreign oil has an impact on economic goals

- economic policies may overlap political party designation

6. 1992 Presidential Election Results

| Candidate | Party | No. of Electoral Votes | No. of Popular Votes (%) |

| William J. Clinton | Democratic | 370 | 44,908,254 (43) |

| George H. W. Bush | Republican | 168 | 39,102,343 (37.4) |

| Ross Perot | Independent | 0 | 19,743,821 (18.9) |

The information in the table best illustrates that

- foreign policy experience mattered most to voters

- “It’s the economy, stupid” resonated with the voters

- NAFTA had little impact on voter behavior

- experience governing at the national level was an electoral advantage

Free Response Questions

- Explain NAFTA and the opposition to it in the 1992 election.

- Explain the factors that led to Bill Clinton’s winning the presidency in 1992.

AP Practice Questions

“We have got to stop sending jobs overseas. To those of you in the audience who are business people, it’s pretty simple: If you’re paying $12, $13, $14 an hour for factory workers and you can move your factory South of the border, pay a dollar an hour for labor, . . . have no health care – that’s the most expensive single element in making a car – have no environmental controls, no pollution controls and no retirement, and you don’t care about anything but making money, there will be a giant sucking sound going south.

. . . When [Mexico’s] jobs come up from a dollar an hour to six dollars an hour, and ours go down to six dollars an hour, and then it’s leveled again. But in the meantime, you’ve wrecked the country with these kinds of deals.”

Independent Candidate Ross Perot, Second Presidential Debate, 1992

Refer to the excerpt provided.1. This excerpt was most directly shaped by

- a policy of economic nationalism

- the success of the Reagan tax cuts

- the nation’s dependence on fossil fuels

- conflict in the Middle East

2. What group would oppose the point of view in the excerpt?

- Environmentalists

- Small-farm advocacy groups

- Advocates of free trade

- Unionized auto workers in the Midwest

3. This excerpted statement was made by a presidential candidate likely to

- secure electoral votes

- win popular votes in industrial areas

- turn off voters in Midwestern states

- expand social safety net expenditures

Primary Sources

Bush, George. “Presidential Debate at the University of Richmond.” October 15, 1992. https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/presidential-debate-the-university-richmond

Suggested Resources

Bennett, David H. Bill Clinton: Building a Bridge to the New Millennium. New York: Routledge, 2007.

Greene, John Robert. The Presidency of George Bush. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2000.

Meacham, Jon. Destiny and Power: The American Odyssey of George Herbert Walker Bush. New York: Random House, 2015.

Wilentz, Sean. The Age of Reagan: A History, 1974-2008. New York: HarperCollins, 2008.