Intro Essay: 1967–Present Day

What progress has been made in the twentieth century in the fight to realize Founding principles of liberty, equality, and justice for African Americans? What work must still be done?

- I can explain why tensions between the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) developed during the 1960s.

- I can explain the emergence of the Black Power ideology and how it led to the formation of new groups and tactics after 1965.

- I can explain the concepts of busing and affirmative action and how they continue the debate over how best to achieve equality for African Americans.

- I can explain how recent outcries over police brutality, discrimination, racism, and the teaching of history have renewed the debate on how to achieve the full realization of liberty, equality, and justice for African Americans.

Essential Vocabulary

| Black nationalism | A school of thought that advocated Black pride, self-sufficiency, and separatism rather than integration. |

| Black Power | A movement emerging in the mid-1960s that sought to empower Black Americans rather than seek integration into white society. |

| Black Panther Party | A political organization founded in 1966 to challenge police brutality against the African American community. |

| Marxism | A social, political, and economic theory originated by Karl Marx that focuses on the struggle between capitalists and the working class; according to Marx, the capitalists exploit the working class, and one day the working class will lead a revolution to seize control of the economy. |

| De facto segregation | Segregation resulting from societal differences such as income rather than imposed by law. |

| Busing | The practice of intentionally moving children to schools outside their school districts in order to desegregate. |

| Affirmative action | A variety of proposed remedies for historic discrimination, such as using quotas to ensure a specific number of applicants from traditionally underrepresented communities to a college or university. |

Where Do We Go From Here? 1967 – Present Day

The 1960s initially saw hard-won gains for the civil rights movement. As the decade continued, however, the movement increasingly fragmented. The legislative achievements of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 did not alter the fact that most Black Americans still suffered virulent racism, lived in segregated neighborhoods, and were denied equal rights.

Five days after the Voting Rights Act became law, rioting broke out in the predominantly Black neighborhood of Watts in Los Angeles, sparked by the arrest of Marquette Frye, a Black man pulled over for allegedly driving recklessly. A violent altercation followed in the wake of his arrest, and it was another 5 days before peace was restored to the city, requiring thousands of police, highway patrol officers, and the National Guard to curb the disturbances. In the end, 34 people died, 1,000 were injured, and 4,000 were jailed. The Watts riots showed that the struggle for equality and justice was far from over. Civil rights activists debated the means and ends of the next phase in the struggle for equality and justice.

Martin Luther King, Jr., brought his campaign for integration through nonviolence to the North. In a 1967 speech to his fellow members of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), King expanded the focus of the civil rights movement to include addressing economic inequality. Despite broadening his focus to include poverty, King remained committed to nonviolence. In his 1967 speech to the SCLC, he said, “Through violence you may murder a hater, but you can’t murder hate through violence. Darkness cannot put out darkness; only light can do that.”

Tensions between King and the SCLC and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) escalated during this period. In 1966, Stokely Carmichael took over leadership of SNCC from John Lewis. Influenced by Malcolm X, Carmichael had already grown disenchanted with the goals of integration and the commitment to nonviolence, and he now espoused Black nationalism. He dismissed SNCC’s few white staffers and was determined to move SNCC away from interracial collaboration.

Malcolm X, seen here (top) in 1964, greatly influenced younger civil rights workers disillusioned by white violence. Stokely Carmichael (bottom) was influenced by Malcolm X and promoted racial pride and independent Black political and economic power.

Also in 1966, activist James Meredith was shot while raising awareness of continued racism and Black voter registration in Mississippi. On June 16, Carmichael continued Meredith’s planned march in Greenwood, Mississippi, and led a group of activists in the chant, “We want Black Power.” The phrase Black Power caught on as a rallying cry of younger, more radical civil rights activists.

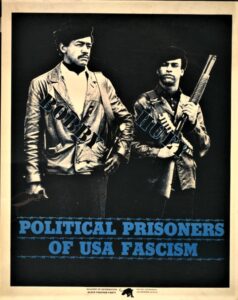

Black Panther Party founders Bobby Seale and Huey P. Newton are pictured in this 1972 advertisement for their party. Newton’s weapon illustrates the group’s belief in armed self-defense.

Carmichael explained the meaning of Black Power in his 1968 book, Black Power: The Politics of Liberation: “It [Black Power] is a call for Black people in this country to unite, to recognize their heritage, to build a sense of community. It is a call for Black people to define their own goals, to lead their own organizations.”

In 1967, Hubert G. Brown succeeded Carmichael as the head of SNCC and increased the militancy of its rhetoric. Black Power evoked fear in many white Americans and contributed further to the break between King and older proponents of nonviolence on one hand, and younger activists who believed in Black separatism on the other. Martin Luther King, Jr., welcomed Black Power’s promotion of Black leadership and cultural pride, but he objected to its belief in Black separatism.

Other young leaders, however, agreed with its different vision for equality and justice. In 1966, Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale formed the Black Panther Party to protect Black residents from police brutality in Oakland, California. The Black Panthers offered a message of self-reliance and self-empowerment, advocated armed self-defense, and used aggressive rhetoric to offer a more radical vision for racial progress. Their message also included sympathy for Marxism and rejection of the free enterprise system.

In 1968, tragedy struck with the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. As the news broke, riots erupted across several cities in the United States. Membership in Black Panther Party chapters nationwide increased substantially. Supporters admired the party’s boldness in opposing police brutality, along with its efforts to improve conditions in urban ghettos by operating schools, healthcare clinics, and free-breakfast programs. Critics, however, pointed to a record of criminality in its leadership. The party disbanded in 1982.

In 2011, President Barack Obama awarded Congressman John Lewis the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Speaking of the award, Lewis said, “People must have the desire to get out there, to push and pull, and to never give up, to never get lost in a sea of despair, but to keep the faith.”

The Supreme Court continued to consider questions of equality and justice. The 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education declared segregation in public schools to be unconstitutional, but many schools remained effectively segregated due to the de facto segregation of neighborhoods across the country. In 1971, the U.S. Supreme Court unanimously declared busing constitutional in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education. Busing intentionally moved children to schools outside their school districts in order to desegregate. Pushback, sometimes violent, occurred across the country, and the legacy of busing is still debated today.

The court also issued a number of decisions on the issue of affirmative action, particularly in college admissions. Critics argue that affirmative action runs counter to the concept of achievement based on merit and can result in discrimination against non-minorities. Proponents argue that the legacies of historic discrimination should be addressed by ensuring that traditionally underrepresented communities have equal opportunity and an equal chance to thrive. Today the question is still debated: Do race-conscious public policies intended to address historic injustices enhance the quest for liberty, justice, and equality, or do they undermine it?

Black Lives Matter Plaza, a pedestrian section of 16th Street NW in Washington, DC, began as a mural as part of protests of police brutality after the death of George Floyd. The plaza was given the official name by DC Mayor Muriel Bowser in June 2020.

The country’s ongoing struggle to realize liberty and equality for all has continued to play out in recent events. For instance, outcries over police brutality, discrimination, and racism in 2013 inspired a new wave of activism in the Black Lives Matter movement. The role of history in education—what is taught about slavery and racism and how it is taught—has also come into the spotlight. In an essay written shortly before his death, Congressman John Lewis encouraged young people to study history to help find solutions to the challenges currently facing the country. In taking on this work, present and future generations in turn must consider the promise of Founding principles and the best means to ensure their faithful application. This challenge has engaged people of all races across U.S. history, and informed by their stories, each generation must do its part to build the nation.

Reading Comprehension Questions

- How did the civil rights movement splinter after 1965?

- Briefly explain the major civil rights issues the Supreme Court took up in the latter half of the twentieth century.

- How does the struggle to realize liberty and equality for all continue today?

- Why did civil rights leader and Congressman John Lewis encourage young people to study history in this struggle?